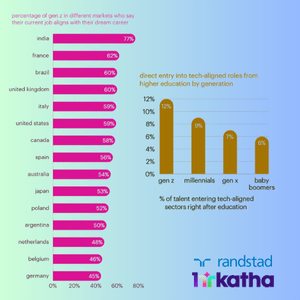

Gen Z enters the workforce with striking clarity about their futures. Eighty-five per cent consider long-term career goals when evaluating new roles—the highest of any generation. In India, 77 per cent describe their current position as a “dream job,” far above the 58 per cent global average.

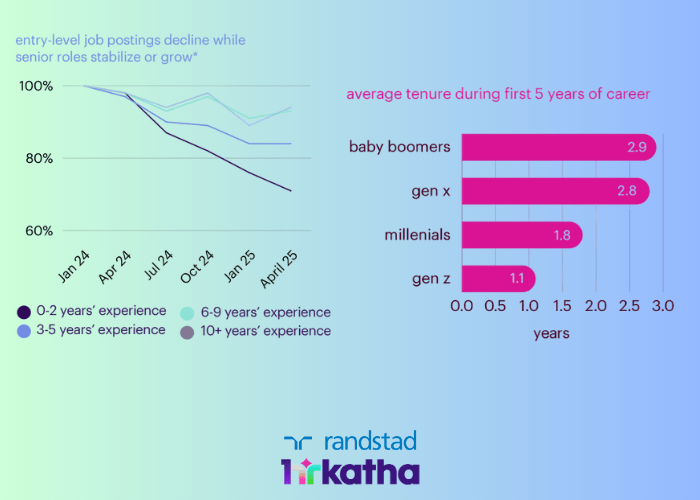

Yet, 54 per cent are actively job hunting. One in three plans to leave within a year. Average tenure stands at just 1.1 years in their first five years of work—compared to 1.8 for millennials, 2.8 for Gen X, and 2.9 for baby boomers at the same career stage.

According to Randstad’s ‘Gen Z Workplace Blueprint’ report, based on a survey of 11,250 workers and analysis of 126 million job postings globally, this isn’t youthful impatience. It’s a rational response to a labour market being fundamentally restructured by AI—without creating the entry points this generation needs.

The Vanishing Ladder

Job postings requiring zero to two years’ experience have dropped 29 percentage points since January 2024. Roles requiring three to five years fell 14 percentage points. Meanwhile, positions requiring 10-plus years held steady or grew. The rungs at the bottom of the career ladder are disappearing while those at the top remain intact.

In technology—Gen Z’s most desired sector—junior roles plummeted 35 percentage points. Finance saw entry-level positions fall 24 percentage points. Only healthcare bucked the trend, rising 13 percentage points driven by urgent need for nurses and medical assistants.

When traditional entry pathways don’t exist, staying 18 months to “build experience” becomes irrational. Why remain in a role teaching skills the market no longer values?

The Confidence-Rejection Gap

Seventy-nine per cent of Gen Z say they learn new skills quickly—the highest confidence of any generation. Yet 46 per cent have been rejected for lacking required skills, compared to 24 per cent of baby boomers. Forty-one per cent lack confidence to find another job—the highest share across age groups.

The gap between perceived ability and market acceptance reveals a cruel irony: Gen Z may indeed learn quickly, but they’re entering a market where even basic roles now require experience they cannot yet possess. Two in five don’t feel they can achieve their dream role due to education barriers. Forty per cent cite personal background as obstacles, nearly twice the 24 per cent of boomers expressing similar concerns.

This self-doubt coexists with high mobility. Even when confidence is low, Gen Z still pursues new roles if their current environment lacks opportunity. They’re not paralysed by doubt—they’re calculating risk while moving anyway.

Dream Jobs They’re Planning to Leave

Forty-four per cent say their current role doesn’t align with their dream career—the highest amongst generations. Thirty-seven per cent already regret their sector choice. Only 60 per cent say employers genuinely care about their future, compared to 76 per cent of baby boomers.

Yet India’s 77 per cent calling jobs “dreams” towers above Japan’s 34 per cent, Germany’s 45 per cent, and Belgium’s 46 per cent. This variance suggests either radically different expectations or different definitions of success.

The compromise appears in values: three in five Gen Z workers would take jobs misaligned with personal values if pay were strong—significantly more than boomers’ 49 per cent. They’re pragmatic, not principled, when financial pressure mounts.

Even while compromising, they deliver: 68 per cent work efficiently. But only 64 per cent feel engaged, and 54 per cent browse for new roles. They perform adequately while plotting exit—redefining what workplace loyalty means.

The 22 Per Cent Exodus and 1.1-Year Reality

Gen Z has a 22 per cent attrition rate over the past 12 months—highest of any generation. The 1.1-year average tenure represents a 38 per cent decrease from millennials’ 1.8 years. Each generation is staying roughly 40 per cent less time than its predecessor. At this rate, the generation following Gen Z might average under a year per role.

Fourteen per cent cite lack of career progression as their strongest exit motivation, second only to pay. Patterns vary by market: India sees 37 per cent planning to leave within a year with 12 per cent staying indefinitely. Japan shows the starkest divide: 22 per cent leaving soon, just 4 per cent staying long-term.

This isn’t random. Markets with rigid hierarchies and slow progression see faster Gen Z exodus. Those with clearer advancement pathways retain better. The message: progression visibility matters more than perks.

The AI Paradox: Enthusiasm Meets Existential Dread

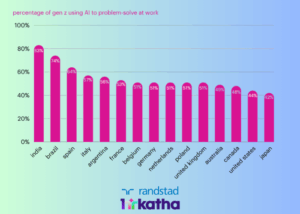

Fifty-eight per cent are excited about AI’s workplace potential. Fifty-five per cent already use AI to problem-solve—the highest rate across generations, up from 48 per cent last year. Indian Gen Z leads globally at 83 per cent, compared to Brazil’s 74 per cent and Japan’s 42 per cent.

Yet 46 per cent now worry about AI’s career impact, up from 40 per cent last year. Anxiety rises as usage increases—direct experience makes the competitive threat tangible. The worry is rational: AI directly caused the 29-percentage-point decline in entry-level roles by automating tasks that once required junior employees.

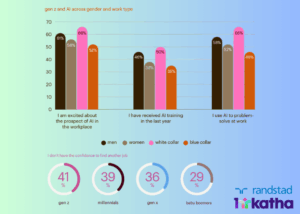

Worse, access isn’t universal. Fifty per cent of white-collar Gen Z received AI training versus 35 per cent of blue- and grey-collar workers. Gender compounds the gap: 46 per cent of men received training versus 38 per cent of women. These disparities create sorting mechanisms—those without training access fall behind, producing inequality within an already disadvantaged generation.

Side Hustles and Fractured Employment

Gen Z is markedly less likely to work single full-time roles (45 per cent) than Gen X (61 per cent) or millennials (60 per cent). Yet only 24 per cent say full-time work is their goal. Amongst those employed full-time, 31 per cent would prefer combining it with a side hustle, while just 22 per cent want traditional arrangements going forward.

The gap between current reality (45 per cent in single roles) and preference (24 per cent wanting it) reveals trapped workers seeking exit—not because they reject work, but because single-employer relationships no longer provide security or growth.

The Tech Migration That Defies Logic

Despite technology sector entry-level postings falling 35 percentage points, Gen Z continues flooding toward it. Tech-aligned industries show a 70 per cent net gain—for every 100 Gen Z workers leaving other sectors, 70 move into technology.

Twelve per cent of Gen Z enters tech directly from higher education, compared to 9 per cent of millennials and 6 per cent of boomers. Direct entry is increasing even as traditional entry-level tech roles disappear.

The answer: entry positions are vanishing, but mid-level roles requiring different skill mixes are emerging. Gen Z with self-taught coding and AI familiarity can sometimes skip junior positions entirely—entering at what would historically be intermediate levels.

This creates winners and losers within Gen Z itself. Those with learning resources leapfrog traditional pathways. Those without find themselves locked out entirely, unable to access vanishing entry roles yet unqualified for reconfigured positions above them.

What Loyalty Looks Like Now

Sixty-eight per cent work efficiently even while job hunting. Previous generations showed loyalty through tenure—staying when frustrated. Gen Z shows loyalty through performance—delivering while planning to leave.

India’s data reveals the tension: 77 per cent call jobs dreams, yet 37 per cent plan to leave within a year. These coexist because “dream job” doesn’t mean “forever job”—it means “right role at this career stage.” When they outgrow it, they leave without guilt.

The 1.1-year tenure isn’t failure—it’s adaptation. In markets where entry roles vanished 29 percentage points in 18 months and AI eliminates learning opportunities, staying longer than necessary would be irrational. Gen Z isn’t less loyal than boomers—they’re operating where loyalty isn’t structurally rewarded. Pensions, seniority systems, and job-hopping stigma have dissolved.

The Unsolved Equation

For employers, the old playbook—hire cheap, develop slowly, promote after years—is dead. The new playbook—hire capable, develop rapidly, promote on results—requires infrastructure most lack. With 22 per cent annual attrition, they’re training workers who’ll leave within 1.1 years, barely time to become productive.

For Gen Z, career management is now core competency. The 55 per cent using AI to problem-solve have advantages over the 45 per cent who don’t. But this creates winner-take-most dynamics, with preparation gaps producing divergence within the generation.

The generation is ambitious, capable, and clear-eyed. The question is whether the labour market they’ve inherited will give them space to realise those ambitions—or whether they’ll spend careers working around its inadequacies. At 1.1 years per role, they’re not waiting to find out.

Comments

Join Our Community

Sign up to share your thoughts, engage with others, and become part of our growing community.

No comments yet

Be the first to share your thoughts and start the conversation!